John Singer Sargent: A Study for Porta della Carta of the Doge’s Palace.

John Singer Sargent was born to expatriate American parents in Florence in 1856. Always in search of culture, his family traveled often throughout Europe, always finding their way back to Italy, the perceived epicenter of all things culturally significant. Even after establishing residency in England in 1886, Sargent returned to Italy numerous times, including annual visits to the country between the years of 1897 and 1914. Sargent took a novel approach to painting the city that had been the inspiration for tourist paintings of the previous two centuries. Instead of highlighting the domes and towers of the city, as was the fashion of the time, Sargent places emphasis on the more mundane architectural elements-,back alleys and doorways, stucco walls and finials – to give a more intimate view of the city, one that was certainly unrecognizable to most tourists. Moreover, John Singer Sargent had an emotional attachment to Italy and felt at home in the country. The figures in his work are most often friends and family, inhabiting neither the loveliest nor the most significant places but rather those that showcase the essence of the city.

One may wonder why if he was so fond of incorporating those he loved in his works, why is this study devoid of figures? Infrared photography undertaken by conservator Bruce Wood unearthed the fact that two figures were outlined and subsequently overpainted at the time of creation. The underdrawing shows two figures, one a woman, possibly with a bustle, and the other unidentifiable, standing on the lower left hand side of the painting, in the area that subsequently became the deterioration on the wall.

Although the idea of eliminating figures in a composition may seem unusual, John Singer Sargent was a perfectionist who had no hesitation omitting elements he did find up to par. Sargent, arguably the premier portrait painter of his generation, believed that it was “..impossible to repaint a head where the understructure was wrong.” and would amend his paintings often when creating studies, only discarding the canvas when the changes became too apparent.

From what is discernible from infrared scans of the work, the manner in which these two figures are rendered is nearly identical to the way Sargent was taught to paint. Sargent trained under Carolus-Duran, who instructed Sargent never to underdraw, only underpaint his canvases. He would begin with sweeping brush strokes and fill in details, beginning in middle tones and moving outward from there, gradually filling in his light and dark tones. Infrared scans of this particular underpainting show the beginning of a developed painting, with a large mass of a neutral color accentuated by both black and white details, further evidence that this may indeed be the work of Sargent himself. Furthermore, one of Sargent’s tenets of painting is to paint figures into another rather than rendering them separately until they touch. In this work, this idea is at play: the figures meld seamlessly into one another, forming shapes that could be the beginnings of bustles or cloaks, arms or shoulders, or faces or chapeaus.

While Sargent is most known for his luminous watercolors of Venice, he also produced a number of oil paintings of the city.

In 1913, he painted a view of the Courtyard of the Scuola Grande di San Giovanni Evangelista, which is now in the collection of the Harvard Art Museums. The painting which is the subject of this analysis is an oil painting of the Porta della Carta of the Doge’s palace, a building Sargent painted multiple times, including one of his most notable paintings, Interior of the Doge’s Palace (1898).

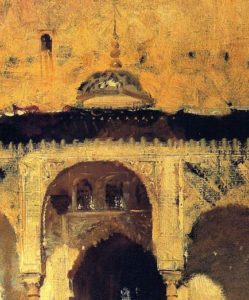

While Sargent often cropped his landscapes and chose unusual points-of-view to accentuate height of buildings or depth in the picture plane, both of these paintings are fairly straight-on compositions. As can be seen in the photos above, the courtyard painting is more detailed, but in both paintings the architecture has been softened and simplified. This aspect of the paintings also relates to Sargent’s oil paintings from previous years. For this example, his 1879 oil painting Alhambra Patio shows similar treatment of details to both of the paintings above.

The method of painting and the style and shape of the brush strokes in all three paintings is very similar, showing a consistency which spans 34 years. All three paintings were created over a dark under-painting. All three are painted with consecutively heavier (thicker) paint, with the highlights being the heaviest. All three have subtle color variations in both the darks and the light areas. All three have a dominant use of dry-brush technique to create atmosphere and blur details.

The paintings also show an impressionistic use of brush-bristle texture in the heavier painted large areas, which corresponds in each to the upper quarter of the painting: The sky and dome in Porta della Carta; The sky in Courtyard of the Scuola; The upper wall of Alhambra Patio.

Several edge-details of each painting are also similar: The ragged edges of the main archways in Alhambra Patio and Porta della Carta; the abbreviated details shown in the bases of walls in Porta della Carta and Courtyard of the Scuola; the way, in each painting, that the artist avoided creating hard edges when painting light areas next to dark ones (There is usually a buffer area of a mid-value color or grey, not covered by the lightest paint, separating them.)

Thickly painted skies can also be seen in Sargent’s two c.1905 paintings of Moab and the Dead Sea.