Rare Gainsborough Study Discovered at Woodshed’s Conservation Studio

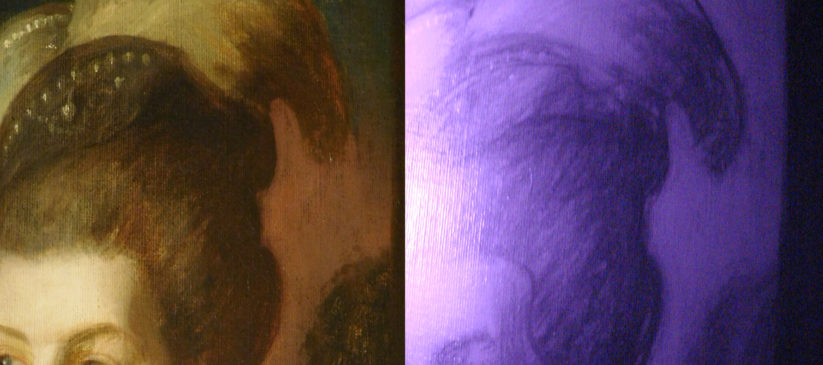

Routine examination of a painting rarely reveals surprises, but one portrait of a beautiful woman led to a cross-Atlantic adventure for oil painting conservator Bruce Wood. Infra-red photography revealed a complex and energetic drawing hidden beneath the surface of the paint.

The painting was initially identified as a copy of the most famous painting in Edinburgh’s Scottish National Galleries: The Honourable Mrs Graham’s full-length portrait created by her admirer, Thomas Gainsborough. However, examination of the under-drawing and comparison of it with Gainsborough’s drawing style, quickly led to the conclusion that the painting’s creation was a precursor to the SNG’s finished work.

The discovery led to examination of another Gainsborough painting hanging in the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, and eventually a trip to Edinburgh to see their masterpiece and perform infra-red photography in their gallery. The revelations of this work led to an understanding of Gainsborough’s working methods, and further bolstered the opinion that the Woodshed’s painting is a rare oil study by the master artist.

Perhaps one of Thomas Gainsborough’s most intricate and recognizable compositions, Gainsborough’s portrait of the Honorable Mrs. Graham is one of the finest examples of 18th century portraiture. Equally as interesting, however, is the story of the sitter, Mrs. Graham, born Mary Cathcart, daughter of the Scottish ambassador to Russia. She spent her early years at the Court of Catherine the Great before her betrothal to Thomas Graham in 1774. Although she maintained a life full of allegations of impropriety, including an alleged affair with Marie Antoinette, Graham was eternally enamored by his wife, going as far as riding ninety miles back to their residence, braving inclement weather to collect jewelry Mary had intended to wear to the ball that night but had forgotten. After her untimely death in 1792, unable to bear the sight of his beloved wife, he turned over ownership of the original Gainsborough painting over to her sister. It was subsequently donated to the Scottish National Galleries by one of her sister’s heirs.

Thomas Graham, however, was not the only one infatuated by Mrs. Graham. Thomas Gainsborough, too, was enamored by her presence and painted her multiple times, mostly from memory. Her striking beauty made her desirable to all and became one of the most admired women of her day, by both men and women alike.

The variation in backgrounds is the clearest indication that this is perhaps a preparation sketch for the more intricate version that hangs in the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art. Gainsborough solidified his position as one of the premier English painters, who dabbled in a variety of prominent styles during his illustrious career. While the exhibited version is a quintessential Gainsborough Rococo landscape, with an undulating, verdant hill and exquisitely rendered trees that would lay the groundwork for British Romanticism in the subsequent decades, this study maintains a more somber, yet equally as striking tone. The bucolic hillscape is replaced with a seemingly opaque mass of darkness capped by an eerie sunset, providing a stark contrast with the delicate, pale white Mrs. Graham rather than seamlessly integrating her into the composition. Although dissimilar from the version that now hangs in the Scottish National Gallery, the background is reminiscent of that in Gainsborough’s 1759 Self Portrait and adds a revolutionary dynamic to the formal, rigid rules for which eighteenth century portraiture is known.

Gainsborough is regarded for his attention to even the most minute details when rendering textures in luxurious fabrics, jewels, hair, and accouterments, among other things. His hair is of particular note, eclipsing that of even his most notable contemporary, Sir Joshua Reynolds. Infrared technology has led to the discovery of how he rendered his sitters’ coiffures in such a dynamic manner- an underlying sketch in black chalk. When highlighted with paint, the quick, vertical strokes of black chalk add to the dynamism of the sitter’s fashionable updo and add depth to the static painting. This technique was peculiar enough to warrant further investigation from conservator Bruce Wood, who found nearly identical underdrawings on not only the version in Scotland but also on Gainsborough’s Haymaker and Sleeping Girl (late 1780s) at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Gainsborough was particularly adept at drawing elegant hands, and this work is no exception. His hands extend from an already elongated wrist and terminate seamlessly into her gown. Although disproportionate, the elongated, clutching fingers only enhance the elegance of his sitters and, rather ironically, aim to pronounce the dainty features of his elite, sophisticated clientele.

While the Woodshed’s portrait is in exceptional condition, it does show signs of its age, furthering the idea that this is indeed a study by Gainsborough! The manner of cracking is consistent with other portraits of the period, including both the version in the National Gallery and his compositions found at the Museum of Fine Arts. This piece is a technical masterpiece that only Gainsborough or someone equally as masterful could have painted, and it is, indeed, very likely that it was created by Gainsborough’s hands.