Gottlieb’s Color Bursts

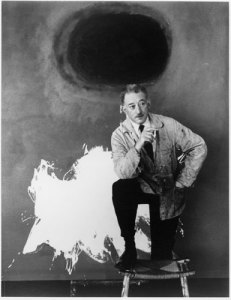

Adolph Gottlieb had three major artistic periods during his long and successful career. Born in New York to Jewish immigrant parents in 1903, by the time he was a teenager it was clear that Gottlieb was destined to be an artist, there was no other choice.

After dropping out of high school, Gottlieb took classes at the Art Students League of New York. In 1921 he worked his passage to Europe on a merchant ship, and travelled through France, Germany and parts of Central Europe. During his six month stint in Paris he visited the Louvre every day, looking and learning.

Upon his return to New York in 1924 Gottlieb painted full time, and formed friendships with fellow artists Barnett Newman, Mark Rothko, David Smith, Milton Avery, and John Graham. The work and philosophy of these friends greatly influenced Gottlieb, and with others they would form the group known as THE TEN. They often exhibited their works together.

Gottlieb’s first solo exhibition was at the Dudensing Galleries in New York City in 1930. His early work can best be described as Expressionst Realist. He also began to be influenced by the Surrealist painters of the time.

I frequently hear the question, “What do these images mean?” This is simply the wrong question. Visual images do not have to conform to either verbal thinking or optical facts. A better question would be “Do these images convey any emotional truth?”

A major break occurred when he moved to the desert in 1937. His work became decidedly more Surrealistic. It is during this period that he painted Sea Chest, a seemingly normal landscape rife with incongruity.

Ultimately Surrealism was not Gottlieb’s metier and he moved on. Influenced by tribal art, Gottlieb began to develop what he called “pictographs” shapes and symbols contained in compartmentalized spaces.

He wanted these icons and symbols to be basic and free of meaning, so that the viewer could respond on a purely visual level.

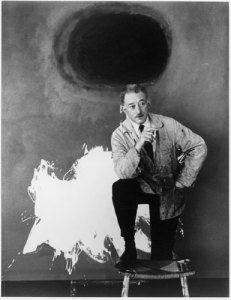

Gottlieb’s most recognizable style finally emerged in the 1950s. His Color Burst works reference what he calls “imaginary landscapes” often with a horizon line, pictographic slashes and symbols below, and a great sun (or moon?) hovering over the horizon.